Hebden Bridge Local History Society

Spinning through the West Riding

Speaker: John Cruickshank

Monday, 15 November 2021

John Cruickshank followed a career as an orthopaedic surgeon by embarking on studies in local history, completing a PhD focusing on the Headingley area of Leeds. Fascinated by the very different nature of the Leeds townships of Bramley, Armley and Wortley, he has now begun to uncover something of the pre-industrial organisation of textile production in this and other areas of the West Riding of Yorkshire.

He told a meeting of the Hebden Bridge Local History Society that studies of the West Riding textile industry made in the first half of the twentieth century have rarely been questioned or updated. The townships John has looked at were producing mainly coloured broadcloth – dyed in the wool, plain woven and cropped to give a short nap. He particularly wanted to focus on the processes involved after dying and before weaving.

Carding or combing

Preparing the wool for spinning required a process of either carding or combing. Carding involved pairs of a kind of wire brush used to straighten the fibres, while combs had much longer spikes to produce a long staple lying in parallel. It has been accepted that cards were used to prepare the yarn for woollen cloth, while combing was needed for the yarn for worsted. However, John's researches challenge that this was the case in the West Riding during the 16th and 17th centuries. The probate inventories of broadcloth producers in and around Leeds had different kinds of comb, but the earliest mention of cards is 1708.

Olive oil from Seville

John explained that the raw wool had to be de-greased ready for dying, and then oil had to be added to make it ready for spinning. Olive oil from Seville used for this purpose is found in inventories as well as rancid butter which served the same purpose. The metal spikes of the combs were heated to apply the oil and straighten the long wool fibres.

Scribbling

What seems to be a Yorkshire invention – the scribbling box – replaced combs at the start of the 18th century. Scribbling is the process by which combinations of different kinds of wool fibres are mixed, cleaned and aligned ready for spinning. John would love to know more about what the boxes looked like, but they were used by children in the domestic setting. Scribbling became one of the first processes to be industrialised, with scribbling mills, but these boxes must have been part of pre-industrial production.

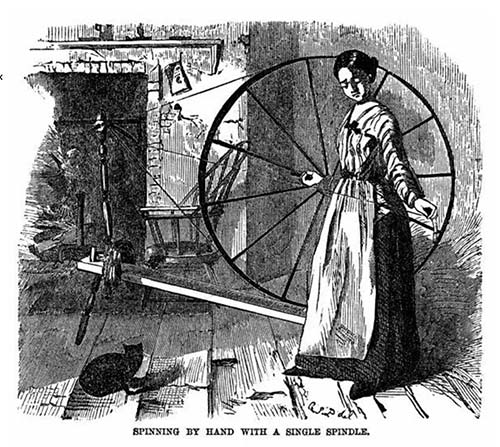

Spinning

Another area which John thinks has been misunderstood is the organisation of spinning. The traditional picture of a small wooden spinning wheel operated by treadle is a line wheel – used to spin flax or hemp for linen production. This would have been too slow for the woollen industry. The wheels that would have been used were much larger and are often identified as 'great wheels' in inventories. These were operated by hand with the twist inserted with a forward movement and the wheel turned backwards to wind the yarn onto a spindle. The very fast spindle movement in the hands of a skilled spinner would be similar to that of the 20th century mule spinning machine and importantly produced yarn of a predictable quality. Wordsworth depicted this in his portrait of the shepherd Michael's wife:

'two wheels she had

Of antique form;

this large for spinning wool

That small, for flax'.

The number of spinners per weaver

This small scale division of labour with a wife spinning yarn for her husband to spin stands in contrast to the estimates made over time about the number of spinners needed to provide yarn for the weavers. The ratio has been estimated as between 4 or 5 spinners per weaver, but there are wide variations and not much confirmative evidence. In the Leeds area between 1688 and 1742 there were 43 looms but only 9 wheels. In the production of broadcloth, most of the spinning was 'put out' to workers at home, with the finished yarn delivered to the weaver. John envisages entrepreneurial women involved in this important and skilled part of the production of wool cloth; but the fact that only widows or spinsters made wills or had inventories of their property goes some way to explain why the tools of their trade are missing from the documentary evidence.

Women spinners

There is also little evidence about how much spinners were paid. It was not a single industry, John pointed out, as it involved different kinds of yarn, and wages would be dependent on place – women workers in particular would not have had the mobility to follow the higher wages. Just around the corner was the industrial revolution and the beginning of the mechanisation of textile production, but these women spinners were more than simple auxiliaries in the domestic industry – they were making a skilled and essential contribution to one of the most important trades in England.

The next meeting of the Hebden Bridge Local History Society is at 7.30 on Wednesday 24th November, in Hebden Royd Methodist Church. Nigel Smith will be talking about his discoveries about the Medieval Park of Erringden. All are welcome; visitors £4, members free.

Further details on www.hebdenbridgehistory.org.uk and on the Facebook pages.