Local History Society Report

Causes and causeys – manorial regulation of roads

Report of talk by Murray Seccombe

Saturday, 15 February 2020

Courts leet, courts baron, pains, amercement, presenters were just some of the technical terms introduced in last Wednesday's well-attended lecture to Hebden Bridge Local History Society, washed down with a dash of legal French, Latin and old dialect words. Murray Seccombe, the Society's secretary, studying for a PhD at Lancaster, shared his experience of using records from the manor of Wakefield to get a fix on how the area's highways were managed in the seventeenth century.

He started with the make-up of this huge medieval manor, stretching from Wakefield to the Lancashire border and taking in most of the parish of Halifax. While many issues of land tenure and management were dealt with in the courts baron of the sub-manors, it was the court leet, meeting twice a year in Halifax, Brighouse, Wakefield and Kirkburton that took on petty crime and infrastructure – which, in the seventeenth century, largely meant its roads and bridges. Petty constables brought repair and nuisance problems to the court to set penalties and deadlines. Murray illustrated the remarkable story of how 6000 of these orders ('pains') had survived intact on paper sheets rolled in parchment wrappers.

He showed how there were clear differences in the patterns of activity across the parish. Tudor laws for appointing 'highway surveyors' and days for unpaid work by folk on the highways never found much of a footing in western parts of the parish, as communities kept to traditional obligations for highways that adjoined or ran through lands they occupied. In Halifax town, there was strict attention to the streets of the central markets area; this was the only township where fines were regularly given for failure to repair. In the townships to the east, coal mining and quarrying disrupted farming, drainage and roads; these townships built up schedules of repairs to be done every Easter and bylaws to prevent trespass over land by colliers and quarrymen.

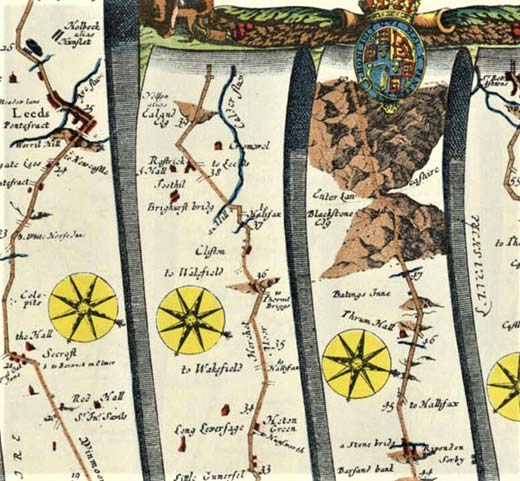

In the upper valley the emphasis was on constables making sure people met their agreed obligations – but also doing the same with neighbouring townships. Sowerby, Wadsworth, Heptonstall and Stansfield sanctioned each other to make sure that routes linking the area with the Lancashire wool towns via Widdop, Stiperden, and Todmorden were kept in order – albeit mainly for travel on foot, by horse or packhorse. Mapping showed communities surprisingly well connected with other parts of the north, quite different from the accepted picture of remoteness.

If this was a system that worked so well, why the signs of decline at the end of the century? Murray's view was that county and township administration was steadily strengthening from the period of the Commonwealth. Townships responded to a new act in 169 by, accepting the re-introduction of surveyors with powers to fund repairs through local taxes. This gave the 'middling sort' of clothiers and farmers a platform to manage roads for their own commercial interests and less incentive to use the court leet.

President of the Society, Barbara Atack, thanked Murray for a thorough and thought-provoking lecture.

Details of the talks programme, publications and of archive opening times are available on the Local History Society website and you can also follow the Facebook page.

With thanks to Sheila Graham for this report

See also