Third series, episode 40

All 132 episodes are available here on the HebWeb.

In the last episode of the current series, there's an offcumden trio, three instances of Murphy's Law, Heptonstall through the ages, two local heroes, the Coiners on the telly, a gig at the museum and a memory of Hebden Bridge before the hippies arrived.

Fare thee well

This is the last of the current series of Murphy’s Lore. It began on the Ides of March, 2022, just after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. I’d met Jonathan Timbers at the Old Gate and he was sure the Russians would win by force of armaments, while I guessed that there would be peace negotiations, and Russia would keep its enclaves and Ukraine would keep its weapons whilst pledging to stay neutral. But Simon Sharma had written that Ukraine wouldn’t lose, because of the spirit of its people. Now, I have edged closer to Sharma’s view.

Putin was threatening to use nuclear weapons. By episode 3, the US diplomat, Fiona Hill, still with a trace of her Geordie accent, had commented, “We are already in the middle of a third World War, whether we recognise it or not.” The Russians had used a lethal weapon in Salisbury, "There was enough nerve agent in that bottle to kill thousands."

Ukrainian women and children became the latest wave of offcumdens into the valley.

Murphy’s Law

Troubles come in threes …

Last week, Jude got a fake fiver in change from a taxi driver.

Then, one Sunday, we were enjoying a cuppa and some rare sunshine on the decking, when …

A heron flew over our garden,

Causing our wows and oh goshing.

"They’re less wild these days,"

We both sagely agreed.

Then it shat all over our washing.

One evening, Kate left out some fruit and opened a can of carnation milk next to it, for a little treat I recall from childhood. I was looking forward to the frisson of a Proustian remembrance of things past, and poured the creamy liquid over the peaches, unexpectedly accompanied by the dead body of a house fly that had nipped into the tin before I got there, and died happy.

Come the offcumdens

The first I knew of ancient, picturesque Heptonstall, I was 14 or so, and was reading Dick Straightup, where Dick bangs his drum for the village. The first time I went there was in the summer of ‘74, having just moved to a flat near Savile Park in Halifax, from where I ran along the canal towpath along the valley before tip-toeing up Hell Hole Hill. That summer Heptonstall seemed like the village featured in our Readers’ Digest book of beautiful villages. Whereas, by late autumn its black gritstone houses and ruined church seemed the ideal setting for a brooding TV murder mystery series.

By the late 70s we had our first car, a fashionable but underpowered 2CV, which Kate managed to chug up to Slack Bottom. Then we walked down to the church, where we found the graves of King David and Sylvia Plath. And in the museum, there was a set of coining tools. In the 80s, we went house hunting in the village, inspecting the preacher’s house next to Mount Zion chapel, a place striking for its tall chimneys on the outside and its mould and damp on the inside. So we turned it down, despite its tempting £16,000 price. The fierce looking preacher ignored us and the agent throughout our visit, preferring to prepare his last sermon.

The Non-Conformist fervour of the past was giving way to earlier pagan passions, and Mount Zion was about to be bought by White Witches, until Cliff Richard, so it’s said, stepped in, bought the chapel and slapped a covenant on it. The hippies were buying up properties in the valley and suspicious locals claimed there were strange goings on in the village graveyard after dark.

A song suggests this might be happening to this day.

The Heptonstall Year

Welcome to our village

We like to celebrate

At Easter there’s a Pace Egg

In Summer there’s a Fete,

Just now we’ve had our Harvest,

And sometimes for a lark,

There’s bacchanalian orgy

In the graveyard after dark.

For a lark (for a lark)

After dark (after dark)

There’s a bacchanalian orgy

In the graveyard after dark.

At our evening classes,

There’s witchcraft and hooray …

'Air frying your placenta

For that special birthing day!’

And when your class has ended,

There’s a warm up round the park,

Then a bacchanalian orgy

In the graveyard after dark.

Round the park, (Round the park)

After dark (after dark)

Then a bacchanalian orgy

In the graveyard after dark.

Local heroes

Reading local histories back in the seventies, I was pleased that Ling Roth and E.P. Thompson had, over the years, represented the working class experience of life during the coining years, redressing the one sided accounts presented in Hansen and other local histories. The terrible murders of taxman Dighton and a potential informer (in a Heptonstall pub), dissuaded readers from a more sympathetic understanding, not just of the coiners, but also the mass of local people, whose cottage industry was being wiped out at that time by large manufacturing mills and child labour.

Local heroes

The Gallows Pole series showed factory owners to be the greatest beneficiaries of coin clipping, which seems a reasonable depiction considering the large amounts of coins being clipped. A future episode might also do well to include a reconsideration of the Bread Riot of June 7th, 1783. The mill owners, and other affluent men who could afford to hoard grain in order to force the price up, published a pamphlet of justification before the execution of the two leaders of the riot on August 16th.

The leader of the Bread Riot was Tom Spencer, Grace Hartley’s brother, the man who organised the killing of Tax Supervisor Dighton, who had been sent north to uncover the identities of the Cragg Vale gang. His right hand man was the young soldier Mark Saltonstall, who I imagine stood out in his red uniform on the day.

What’s known about Saltonstall is he was 'taken from his parents when forty weeks old by relations and brought up by them till 1782, when aged 17 he enlisted in the army.' His regiment was eventually disbanded and he returned home to a valley that was full of people who were half starved. He was persuaded by Spencer to join him in an attempt to seize the corn which was being held in storage in Halifax (as EP Thompson would have it, to force up its price). Spencer might have known that his part in these actions endangered his own life, but he hoped that Saltonstall would help him maintain order amongst the mass of their followers.

On the day, the landlord of the Boar’s Head Inn could not be persuaded to release the corn belonging to its wealthy owners at a fair price. So Spencer and Saltonstall organised their followers into two rows and marched them like soldiers to take the corn and wheat in a peaceable manner from the carts that were due to arrive in town that day. A large quantity was seized and sold to the multitude at the previous year’s price, and the money was given to the carters to hand on to their masters.

Spencer and Saltonstall were subsequently arrested for their part in this bloodless riot. They were tried at York and then hanged on Beacon Hill, close to the spot where Dighton’s murderers hung in gibbets, with their fleshless right hands pointing towards the place where they shot their victim. Knowing the sentiment of the people, family and friends were allowed to take the leaders of the bread riot away for a decent burial.

Years later, a Mr Howarth of Mytholm described the scene he witnessed that day. "The hill side on which the scaffold stood, was white with the upturned faces of the thousands who had flocked from the valleys in which none were left but children and extreme old age.’"

The Leeds Intelligencer recorded that Spencer, 'a tall slender man,' made a short speech to the populace, declaring that he 'did not, on the word of a dying man,' break into the food stores, for which he been falsely charged. His noose slipped when he was hanged, and his body came to the ground, 'but the executioner was so expert that he speedily fixed him in his former situation.'

Mark Saltonstall was described as 'a stout young man,' who appeared penitent. According to Mr Howarth, he was 'impressed with the horrible nature of this public death, and in the face of countless multitudes – many of whom he had known, and who knew him – he wept and prayed devoutly.'

A mass of people thronged the narrow road that led from Halifax to Mytholmroyd. The Leeds paper reported that, "Old people stood at their doors with uplifted hands … At Mytholmroyd Bridge a halt was made; and, accompanied by the moans and lamentations of his friends, the coffin containing Spencer’s body was taken out and carried across the bridge to Hall Gate, followed by an anxious and awe-struck multitude. Here it was laid in a small room close to the road."

In later years, Leyland, a local historian, collected notes on the Coiners and met with a Mrs Walton, who "witnessed a sight which she never effaced from her memory." His aged informant noticed the distorted and hideous features of the man she had recently known in life; "his neck was swollen to a level with his chin."

As for Mark Saltonstall, the Intelligencer reported that the cart and his coffin were halted at The Hole in the Wall before climbing the Buttress, no doubt to refresh both horses and followers.

"The people of Heptonstall, and the inhabitants of the farmsteads that were scattered over the surrounding heights, seated on the slopes, and crowding the tortuous and narrow way which led to the church of St. Thomas the Martyr, waited in pitying sadness, the arrival of Saltonstall’s body, and as it neared the place, the crowd thronged the road, raising their hands with loud murmurings and lamentations that were carried afar by the winds that rarely cease in these northern heights. His home was reached; and, after a few days of mourning, his coffin was carried through the porch of St. Thomas’s Church – past the grave of David Hartley – where the funeral service was said, and Saltonstall was buried with Christian rites."

The Coiners on the telly

Some people round here seemed to dislike The Gallows Pole, a prequel to the events covered in Ben Myer’s novel, but the three writers I met in the days after the first episode were fans of Shane Meadow’s witty and visually striking programmes. As was Ben Myers, who has written that it has changed his life, and most newspaper reviewers.

Back in 1980 at YTV, I pitched a drama I had half written, entitled, The Cragg Vale Coiners, with a recommendation from Stan Barstow. Michael Scarborough, the Commissioning Editor, reckoned that unfortunately, most people knew nothing of this bit of Yorkshire history, and he didn’t think he could get backing from other regional ITV companies. He asked me if I was interested in writing soaps, and I startled him by saying "I can’t stand soaps." Which was a reckless but honest comment. It was years before I realised that the remark was an ill-considered adrenaline hit for me, produced by the ADHD I didn’t know I had.

Mind, even the great Sally Wainwright didn’t thrive at YTV, and I think what the Coiners history needed was an award winning novel to attract a director such as Shane Meadows and familiarise people (especially Commissioning Editors) with this dramatic story, which occurred against the background of a turning point in our industrial history.

TV awards

Sarah Lancashire finally received her richly deserved Best Actress award for her performance as Catherine Cawood in Happy Valley, and a Fellowship to go with it.

Sally Wainwright is writing a new 'change of life' series about five, fifty something, women who form a feminist rock band in Hebden Bridge. So look out for more awards - and tourists - in the near future.

Gigging at the Museum

The Offcumdens, previously known as The Calder Valley Poets, made their post Lockdown reappearance, thanks to an invitation from Museum organiser Nicola Jones. The intimate venue, at one time a grammar school, was packed and, doing my own unscientific vox pop, all had a great time, including the trio.

My friend and former colleague, Pat Monday of Blackshaw Head, wrote:

“It was a great night, George. So much of the best medicine – laughter. Thanks to The Offcumdens and Miss Airedale.”

Readers write

Readers write

Memories of Hebden

Thanks to Andrew Smith, of Smithery and photography fame, for giving me a copy of a book from David Clough, who captured a time and place in his book Tumbletown (2017).

Ah Sed

Wot ah sed

An not that as

You sed ah sed

An you shoon’t

‘ave sed as

Ah’ve sed that as

Worn’t sed.

So look on!

Ah’ve sed

Wot ah’ve sed

An’ th’ers

Ne’er more

To wot

Ah sed.

So nuff sed!

‘For Great Aunt Lizzie’

The author remembers visiting Hebden in 1960, when it looked like a "black and white, British made B Movie. I was from just down the line in Rochdale, which looked like New York in comparison, with its bustling sense of purpose.”

At the age of thirteen, David heard Acker Bilk, and after that he lived for trad jazz, and bought a clarinet, which he learned to play on truanting visits to the "soot blackened walls of Hebden Bridge, and by the time I was 14 I was playing along with revivalist jazzy bands." He learned to play his music from the Deep South of America on "the empty railway station platform in Hebden Bridge."

Ten years later the hippies arrived.

Bye for now

This is the end of Series 3 of Murphy’s Lore. Thanks for the many positive comments I have received from readers over the last four years, and other writers who have shared their own contributions. I have some other projects to pursue for a while, including The HebWeb Interview, if my indefatigable Editor allows.

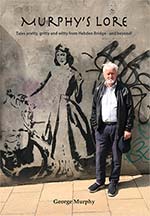

Murphy's Lore, the book, is available to order here

If you would like to send a message about this piece or suggest ideas, email George Murphy

More Murphy's Lore

See the Murphy's Lore home page for all 132 episodes.